Become GERMAN

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

AUTHENTIC GERMAN LIVING

From its unification in 1871 under Otto von Bismarck to its central role in shaping modern Europe, Germany has been a driving force in global history. Its legacy spans centuries, marked by groundbreaking contributions to science, philosophy, music, and industry. From the poetic Romanticism of Goethe and Schiller to the transformative ideas of Einstein and Kant, Germany’s cultural and intellectual heritage is unmatched. Its landscapes, ranging from the Black Forest to the Bavarian Alps, provide a backdrop to a nation steeped in tradition yet embracing innovation.

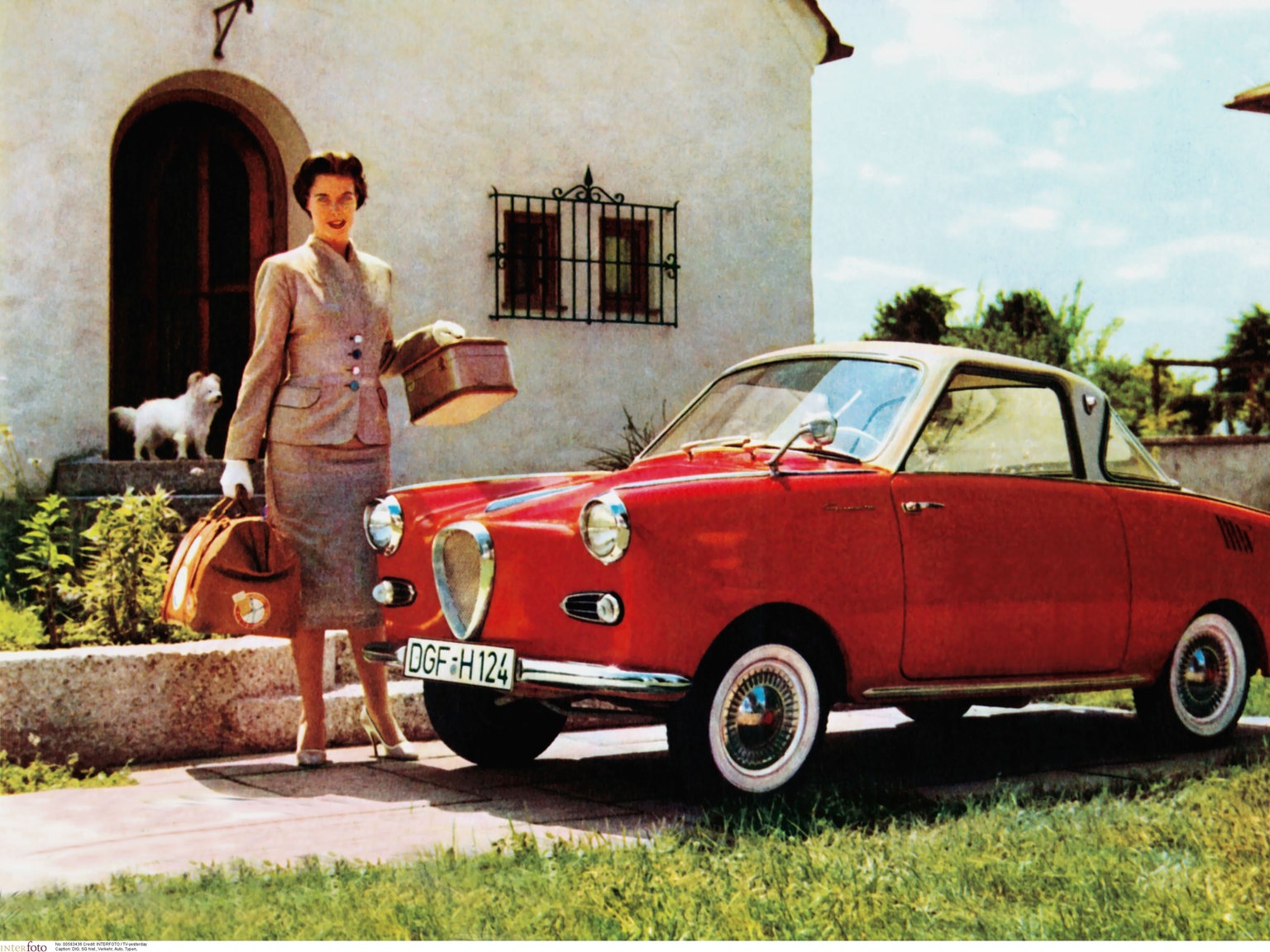

After reunification in 1990, Germany emerged as a global leader in economic and political spheres. A founding member of the European Union and the engine of its economy, Germany champions innovation, sustainability, and cultural exchange. Its vibrant cities like Berlin and Munich, coupled with its focus on education and green energy, reflect a nation that respects its past while building for the future. Today, Germany is celebrated for its precision engineering, rich culinary traditions, and commitment to progress.

We have curated a collection of cultural insights to help you navigate the unique German way of life, teaching you German words and phrases that textbooks and courses often overlook, so you can connect with its culture on a deeper level.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning German, we recommend that you download the Complete German Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any other textbook so you can amaze your German-speaking friends thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your German listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking German today!

ABENDBROT

Abendbrot (evening bread) refers to a traditional German evening meal centered on cold foods, simple preparation, and daily routine. It remains a defining feature of domestic life across Germany, reflecting historical eating patterns and cultural norms surrounding family time, nutrition, and work schedules. The meal typically consists of sliced bread, spreads, cheeses, and cold cuts, and it contrasts with the hot midday meal that historically dominated the day. Although modern work habits have changed eating patterns for some households, the concept continues to hold strong cultural value.

In many regions, the foundation of this meal is Brot (bread), especially dense and nutritious varieties such as Schwarzbrot (dark rye bread) or Bauernbrot (farmhouse bread). These breads developed as practical staples suited to long storage, reflecting agrarian traditions and regional grain availability. The bread is commonly accompanied by Aufschnitt (cold cuts), which may include ham, salami, or cured meats. These items represent long-standing preservation methods such as salting and smoking, important in German food history before refrigeration became widespread.

Cheese also plays a consistent role, often served as Käse (cheese), ranging from mild regional varieties to stronger alpine styles. Alongside cheese and meats, spreads such as Quark (fresh dairy spread) and Obazda (Bavarian cheese spread) appear frequently, each reflecting local agricultural production. Vegetables like cucumbers, tomatoes, and radishes are common additions, tied to the tradition of fresh garden produce and seasonal availability. These elements underline the practicality and nutritional balance typical of the meal.

The social context of Abendbrot is equally significant. The meal is often linked to Feierabend (time after work), a culturally important period dedicated to rest and personal life. Because preparation is minimal, it supports an emphasis on slowing down after work and spending time with family. This connection highlights broader values associated with Gemütlichkeit (cozy sociability), which continues to shape domestic and community interactions throughout Germany.

In some areas, Abendbrot appears in specialized forms influenced by regional customs. In Bavaria or Baden-Württemberg, elements traditionally found during Vesper (light meal with cold foods) may be integrated into the evening setting. In northern regions, fish-based items such as Fischbrötchen (fish sandwich) can appear, revealing the influence of maritime food culture. These variations illustrate how geography shapes local eating traditions while maintaining the structure of a cold, bread-centered meal.

ABITUR

Abitur (final secondary school examination) is the German qualification that certifies completion of upper-level secondary education and grants eligibility for university admission. It represents both an academic milestone and a regulatory mechanism for higher education access across Germany’s federal states. While the structure varies slightly from one state to another, the purpose remains consistent: to assess whether students have achieved the competencies required for academic study. The qualification is issued after several years of coursework combined with standardized written and oral examinations, forming the culmination of the Gymnasium (academic secondary school) track or its equivalent pathways.

The modern system reflects long-standing traditions in German education. Instruction leading to the Abitur emphasizes analytical thinking, structured reasoning, and broad subject exposure. Students typically select a set of Leistungskurse (advanced courses) in which they specialize and receive more intensive tuition. These subjects commonly include German, mathematics, sciences, foreign languages, or social sciences. Alongside these, students continue with Grundkurse (basic courses), ensuring a general academic foundation. The balance between specialization and breadth aligns with German educational principles that prioritize depth of knowledge while preserving comprehensive learning.

Assessment procedures are central to the qualification’s credibility. Examinations typically include multiple written components supervised under standardized conditions, followed by at least one mündliche Prüfung (oral examination). The subjects tested depend on student choices, but German and mathematics appear frequently due to nationwide expectations. The grading system uses the established point-scale approach, where cumulative results determine the overall Abiturnote (final Abitur grade), which directly influences university admissions. Universities may require higher grades for competitive programs such as medicine, engineering, or law, linking performance with future academic trajectories.

Regional differences exist but operate within a harmonized framework. Each federal state administers its examinations through the Kultusministerium (state ministry of education), which sets specific requirements while adhering to national guidelines for comparability. This federal structure ensures both regional autonomy and nationwide recognition of the qualification. Efforts toward harmonization, known through processes like the Bildungsstandards (educational standards), aim to reduce variations and support equal opportunities for students across the country.

The credential is closely connected to Germany’s reputation for rigorous education and supports pathways linked to the Mittelstand (small and medium-sized enterprises), research institutions, and public administration.

ALMABTRIEB

Almabtrieb (ceremonial cattle drive) refers to the traditional autumn event in alpine regions of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland in which cattle are brought down from high mountain pastures after the summer grazing season. Although primarily associated with pastoral agriculture, the custom has developed into a culturally significant celebration. It marks the end of the Almsommer (summer on the alpine pasture), when herds graze on nutrient-rich alpine meadows. The return of the animals to the valley is accompanied by decorated cattle, regional music, and community gatherings, reflecting both agricultural rhythms and long-standing alpine traditions.

The event has deep agricultural roots. During the summer months, herders known as Senn (alpine dairyman) care for the animals in remote high-altitude pastures and produce regional products such as alpine butter and cheese. The grazing on mountain vegetation contributes to the production of Alpkäse (alpine cheese), which holds protected status in certain regions due to its characteristic flavor profile derived from diverse mountain flora. When autumn temperatures begin to fall and weather becomes unpredictable, the Almabtrieb signals the safe return of the livestock to the valley barns, where they will remain through the winter months.

A distinctive feature of the celebration is the elaborate decoration of the cattle. When the summer season has passed without accidents, the lead cow, called the Kranzkuh (crown cow), is adorned with ornate floral headdresses, mirrors, and intricately crafted ornaments. These decorations symbolize gratitude for a safe season and protection during the journey downhill. In contrast, if misfortune has occurred during the summer, the procession takes place without decorations, following the principle known as Stille Fahrt (silent procession), underscoring the ritual’s symbolic dimension.

The Almabtrieb is also closely connected to rural community life. In many villages, the return of the herds is welcomed with local festivals featuring music, regional costumes identified as Tracht (traditional folk costume), and foods typical of alpine agriculture. Visitors often participate in market activities where producers sell cheese, cured meats, and handcrafted goods. The practice strengthens regional identity and supports tourism, particularly in Bavaria, where the event forms part of the broader cultural landscape of alpine traditions.

Environmental and agricultural considerations also shape the custom. Mountain pasture grazing contributes to the maintenance of high-altitude ecosystems by preventing overgrowth, supporting biodiversity, and sustaining cultural landscapes known as Kulturlandschaft (managed cultural landscape).

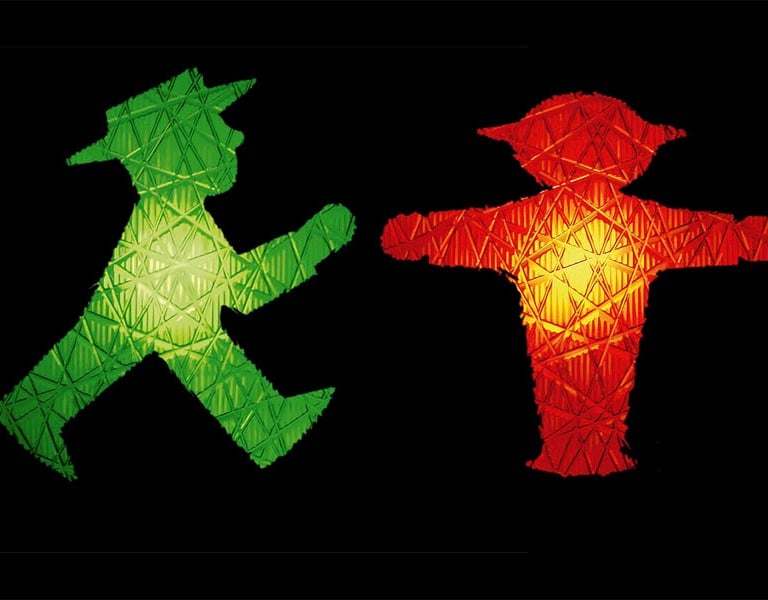

AMPELMÄNNCHEN

Ampelmännchen (pedestrian traffic light figure) refers to the stylized human icon used in pedestrian signals in the former East Germany and now widely recognized as a cultural symbol of German design history. Created in 1961 by traffic psychologist Karl Peglau, the figure was developed to improve road safety by providing a clear, easily interpretable signal for pedestrians, including children and elderly individuals. The design uses a distinctive hated silhouette, which made it visually unique compared to the more generic figures used internationally. After German reunification, the symbol gained renewed appreciation as an element of regional identity and cultural continuity.

The design was part of a larger effort to reform traffic communication during a period of increasing urban motorization. Peglau introduced the icon alongside the concept of Verkehrspsychologie (traffic psychology), emphasizing how visual clarity and recognizable shapes could influence pedestrian behavior. The illuminated red and green figures were intentionally expressive, with the red version standing firmly with outstretched arms and the green version shown in a dynamic walking posture. These characteristics helped the Ampelphase (traffic light phase) become more intuitive for users, especially at busy intersections.

During the decades of the German Democratic Republic, the Ampelmännchen became an everyday presence in cities. Its widespread familiarity made it a quiet but constant component of daily routines, reinforcing norms of Verkehrserziehung (traffic education) taught in schools. When reunification occurred in 1990, there were initial efforts to standardize traffic symbols across the country, and the East German figure faced replacement by the West German design. Public resistance, however, prompted campaigns for its preservation, reflecting the figure’s symbolic value and the growing sentiment known as Ostalgie (nostalgia for East Germany).

The figure eventually gained protected status in certain regions, and today it appears not only in traffic lights but also in merchandise and cultural branding. Businesses frequently incorporate it into products such as stationery, clothing, and souvenirs, transforming the once utilitarian signal into a recognizable emblem of Berlin and the eastern federal states. This commercial presence demonstrates how public infrastructure symbols can evolve into broader cultural artifacts through collective memory and identity.

Comparative studies of pedestrian symbols often reference the figure when discussing effective communication strategies in Stadtverkehr (urban traffic), particularly its ability to convey meaning quickly and universally without textual explanation. Today, pedestrian lights using the Ampelmännchen remain fully functional elements of city infrastructure, especially in Berlin, Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia.

AUTOBAHN

Autobahn (motorway) refers to Germany’s federal controlled-access highway network, known for its engineering standards, extensive reach, and sections without mandatory speed limits. Developed throughout the twentieth century, the system forms the backbone of national transportation infrastructure. It connects major metropolitan regions, industrial centers, and border crossings, supporting both domestic mobility and international freight corridors across central Europe. The network operates under the designation Bundesautobahn (federal motorway), reflecting its administration at the national level rather than by individual federal states.

The origins of the Autobahn extend to early interwar experiments in road construction and high-speed travel. By the 1930s, planners focused on constructing long, uninterrupted routes designed exclusively for motor vehicles. Innovations included grade-separated interchanges, restricted access points, and standardized lane widths. The focus on engineering quality contributed to the development of Richtgeschwindigkeit (advisory speed), a recommended speed of 130 km/h introduced later to guide drivers despite the absence of mandatory limits on many stretches. These design choices made the system a reference point for motorway construction in other countries.

The technical structure of the Autobahn emphasizes durability and safety. Many sections use reinforced concrete or multilayer asphalt designed to withstand heavy freight traffic, known as Schwerlastverkehr (heavy goods traffic). Median barriers, emergency lanes, and controlled entry ramps contribute to accident prevention, while modern expansions incorporate noise-reduction walls and wildlife crossings. Traffic monitoring systems, grouped under Verkehrsleittechnik (traffic control technology), adjust speed recommendations, manage lane closures, and provide real-time information during congestion, construction work, or adverse weather conditions.

From an economic perspective, the Autobahn is crucial for Germany’s export-oriented economy. It facilitates the movement of goods between industrial hubs, ports, and neighboring countries, supporting logistical chains associated with automotive manufacturing, machinery production, and the Mittelstand (small and medium-sized enterprises). Freight companies depend on predictable transit times, and the network’s high-capacity design helps maintain efficiency within Europe’s largest economy. The system is also significant for cross-border trade, linking to the wider European motorway system through strategic corridors.

Environmental and policy debates shape contemporary discussions about the Autobahn. Some regions advocate extending mandatory speed limits to reduce emissions and enhance safety, while others emphasize the symbolic and practical value of unrestricted driving. Infrastructure maintenance, financed through federal budgets and revenue streams such as the Lkw-Maut (truck toll), remains a major political topic due to the high cost of repairs and modernization. At the same time, new projects incorporate ecological considerations, such as habitat protection and noise reduction measures, reflecting evolving transportation priorities.

The Autobahn also holds cultural significance. For many drivers, it represents the concept of Fahrvergnügen (joy of driving), associated with smooth road surfaces, long-distance mobility, and high-performance vehicles.

BIERGARTEN

Biergarten (beer garden) refers to an outdoor drinking and dining area that originated in Bavaria during the nineteenth century and later spread throughout Germany. It is characterized by communal seating, shaded areas, and the service of beer alongside simple regional foods. The Biergarten developed as a response to brewing regulations that restricted breweries to producing bottom-fermented beer only in cool seasons. To meet demand during warmer months, breweries stored beer in cellars covered with gravel and shaded by trees. This practice led to the establishment of outdoor spaces above the cellars where guests could drink beer directly at the source, forming the foundation of the Biergarten tradition.

The sociocultural environment of the Biergarten is rooted in values associated with Geselligkeit (social conviviality), emphasizing shared space, relaxed interaction, and community inclusion. Seating arrangements typically use long wooden tables and benches where visitors sit side by side with strangers, fostering openness and informal conversation. This communal style aligns with broader Bavarian customs and contributes to the perception of Biergärten as democratic spaces welcoming to individuals, families, and groups. The atmosphere is reinforced by the presence of Kastanienbäume (chestnut trees), traditionally planted for shade and now iconic in the aesthetic of classic beer gardens.

Food offerings form another key aspect of the experience. Many Biergärten serve items typical of regional cuisine, such as Weißwurst (white sausage), Brezel (pretzel), and Radi (spiral-cut radish). At the same time, a distinctive tradition permits patrons to bring their own food, known as Brotzeit (snack meal), while purchasing beverages on site. This custom reflects historical regulations designed to encourage fairness among food vendors and breweries. The combination of purchased and self-brought foods contributes to the informal, inclusive nature of the setting, reinforcing the Biergarten’s role as a place for leisurely gatherings.

Beer served in traditional Biergärten often includes varieties such as Helles (light lager), Dunkel (dark lager), or Weizenbier (wheat beer), poured into characteristic glassware like the Maßkrug (one-liter beer mug). The practice of serving beer in large, standardized glass containers emerged from brewery traditions and contributes to the recognizable visual identity of Bavarian beer culture. Some Biergärten operate directly alongside breweries, maintaining historical connections to local production and reinforcing the cultural association between beer, craftsmanship, and regional identity.

Regulation and seasonal patterns shape the operation of Biergärten. Many function primarily during spring and summer, aligning with outdoor leisure and tourism cycles. They must comply with local guidelines concerning noise, seating, and alcohol service, influenced by the Gaststättenverordnung (hospitality regulation) in each federal state. Despite regulatory frameworks, Biergärten maintain a relaxed atmosphere that appeals to residents and visitors alike. Their role as social hubs is reinforced through events, live music, and community festivals held on the premises.

BREZEL

Brezel (pretzel) refers to a traditional German baked good shaped into its characteristic looped form and recognized for its glossy brown crust and soft, chewy interior. It is closely associated with southern Germany, particularly Bavaria and Swabia, and forms an essential part of regional food culture. The typical appearance results from dipping the dough in a lye solution before baking, a process central to its identity. The Brezel appears in a wide range of settings, from everyday breakfasts to large public festivals, illustrating its versatility and long-standing cultural presence in German-speaking regions.

The production process reflects regional baking traditions. The dough is usually made from wheat flour, water, yeast, and salt, shaped into the distinctive twist, and dipped briefly into Laugenlösung (lye solution) before baking. This step produces the characteristic color, flavor, and texture of the crust. The finished product is often sprinkled with Grobsalz (coarse salt), although variations include seeds such as sesame or poppy. In many areas, master bakers maintain strict standards related to size, texture, and baking time, demonstrating the importance of craftsmanship in traditional German bakery culture.

The Brezel plays a prominent role in regional customs and daily meals. In Bavaria, it frequently accompanies Weißwurst (white sausage), typically served in the morning, highlighting its place in local culinary routines. In Swabia, a softer, airier version known as Schwäbische Brezel (Swabian pretzel) is widely consumed and distinguished by its thinner arms and thicker belly. The baked good is also sold in beer gardens alongside Bier (beer), reinforcing its role in leisure environments. These variations illustrate how regional preferences shape both form and preparation techniques.

Historically, the Brezel carries symbolic value. Medieval guilds associated the shape with religious symbolism, and pretzels were often given during fasting periods or festive occasions. Monasteries played a significant role in early production, contributing to the spread of the baking technique. Over time, Brezeln became common in marketplaces and urban bakeries, reflecting increasing urbanization and the development of standardized baking practices. The association with baker guilds is reflected in the Bäckerzeichen (bakers’ sign), which often incorporates pretzel imagery.

During Oktoberfest and other festivals, large versions called Riesenbrezeln (giant pretzels) are sold, highlighting commercial and cultural significance. Many cities hold events or competitions related to traditional baking, reinforcing community identity and sustaining interest in regional food heritage.

BRÖTCHEN

Brötchen (bread roll) refers to the small, individually portioned bread rolls that form a central component of German breakfast culture and everyday meals. They are widely consumed across all regions of Germany and represent one of the most recognizable elements of the national bread tradition. Brötchen vary in shape, crust, and flour composition, reflecting the diversity of regional baking practices. Their role in daily routines highlights the importance of fresh bread in German households, where visiting a bakery each morning remains common in many communities.

Production methods reflect craftsmanship seen throughout German baking. The dough is typically composed of wheat flour, water, yeast, and salt, though some variants incorporate mixed grains. The shaping process often includes scoring the dough with a cut known as the Schnitt (bread roll slash), allowing steam to escape and forming the characteristic crust pattern during baking. Bakers frequently rely on long fermentation techniques known as Teigruhe (dough resting period), which enhance flavor and texture. These technical processes connect modern production with longstanding artisanal traditions within German bakery culture.

Regional varieties of Brötchen illustrate local preferences. In northern Germany, the common term is Rundstück (round roll), a name with historical roots in coastal cities. In Bavaria, a widespread variant is the Semmel (southern bread roll), recognized by its star-shaped scoring. In Swabia, consumers often choose Wecken (elongated roll), while in Berlin, the local form called Schrippe (Berlin-style split roll) features a distinctive central crease. These differences reflect both linguistic diversity and regional baking identities, demonstrating how everyday food items vary across the federal states.

The Brötchen is central to breakfast and evening meals. It commonly appears during Frühstück (breakfast), paired with butter, jams, cold cuts, cheeses, or spreads. During the evening meal known as Abendbrot (evening bread meal), Brötchen may be served alongside other types of bread, supporting the idea of simple, cold meals typical in many German households. In workplaces and schools, the Brötchen is a popular item for packed meals or quick snacks, contributing to its status as an accessible, portable food staple across age groups and professions.

Culturally and economically, Brötchen reflect the strength of the German bakery sector. Many towns maintain multiple independent bakeries, known as Bäckerei (bakery), where daily production emphasizes freshness. Consumers often value crispness and aroma, creating expectations that rolls be purchased shortly before consumption.

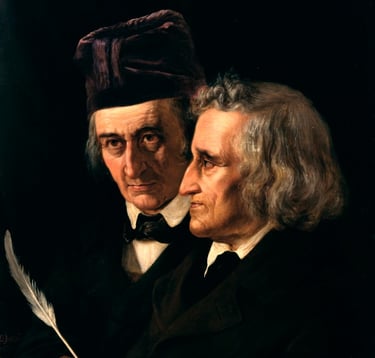

BRÜDER GRIMM

Brüder Grimm (Brothers Grimm) refers to Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, the German scholars whose work in the nineteenth century profoundly shaped fields such as linguistics, folklore studies, and literary scholarship. They are best known internationally for their extensive collection of folk narratives, but within academic contexts they are equally significant for contributions to philology and the study of German language history. Their work reflects an era of intense interest in national identity, oral tradition, and comparative linguistics, positioning the brothers at the center of intellectual movements within German-speaking Europe.

The brothers began their careers as scholars of Germanistik (German studies), focusing on medieval texts and historical linguistics. Their research contributed to the systematic analysis of language development, culminating in the monumental Deutsches Wörterbuch (German dictionary), an encyclopedic work documenting vocabulary, etymology, and usage. Although the project spanned generations and was completed long after their deaths, its structure reflects the methodological rigor they established. Their linguistic research also produced Grimmsches Gesetz (Grimm’s Law), a principle describing consonant shifts in Indo-European languages and considered foundational in historical linguistics.

Their enduring popularity derives from their role as collectors of folk narratives known as Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales), first published in 1812 and expanded in subsequent editions. The collection sought to preserve oral storytelling traditions during a period of accelerating social and cultural change. Many narratives were gathered from informants connected to local traditions, often shaped by rural life, moral instruction, and communal memory. Stories such as “Hansel and Gretel,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” and “Snow White” reflect broader patterns in European folklore and demonstrate how oral narratives adapt across time and region.

The Grimms’ editorial approach balanced preservation with adaptation. Early versions of the tales retained linguistic features characteristic of oral storytelling, but later editions underwent stylistic revisions to meet expectations of family readership. This process included modifications to narrative structure, reduction of certain violent elements, and incorporation of clearer moral themes. The evolving editions illustrate how the brothers negotiated between documenting authentic oral tradition and responding to cultural norms of nineteenth-century society. Their editorial decisions continue to inform debates in Volkskunde (folklore studies) and literary criticism.

Beyond their scholarly work, the brothers were active participants in intellectual and political life. They belonged to the Göttinger Sieben (Göttingen Seven), a group of professors who protested constitutional violations in the Kingdom of Hanover and were subsequently dismissed. This event strengthened their symbolic status within discussions of academic freedom and civic responsibility. Their engagement with political issues reflects the broader context of German unification movements and the pursuit of cultural cohesion through language and scholarship.

Institutions such as the Grimmwelt (Grimm World Museum) in Kassel highlight their role in shaping German cultural heritage. Through their combined contributions to language, literature, and folklore, the Brüder Grimm maintain a lasting presence in public consciousness.

BURSCHENSCHAFT

Burschenschaft (traditional student fraternity) refers to a type of student association established in German-speaking universities in the early nineteenth century, closely linked to emerging national movements, academic identity, and political activism. Unlike social fraternities focused primarily on leisure, the Burschenschaft historically emphasized ideals of unity, academic integrity, and civic responsibility. These organizations arose during a period marked by the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars and growing interest in national cohesion among students. Their formation was tied to the pursuit of Vaterlandsliebe (patriotic devotion), shaping their early political and intellectual goals.

The origins of the Burschenschaft are connected to the founding of the Urburschenschaft (original Burschenschaft) in Jena in 1815. This group sought to unite students from various German states under shared values, rejecting regional divisions present in older student corporations. Their activities included public lectures, celebrations, and participation in broader political movements. Members valued Freiheitsstreben (striving for freedom), an ideal expressing their commitment to constitutional rights and national unity. These principles placed the associations at the forefront of early student political engagement.

During the nineteenth century, Burschenschaften became visible participants in major political events. Their presence at the 1817 Wartburg Festival reflected a symbolic protest against reactionary policies, while their role in the 1832 Hambach Festival highlighted participation in democratic and nationalist demonstrations. Governments responded with restrictive measures such as the Karlsbader Beschlüsse (Carlsbad Decrees), which targeted student activism and academic freedom. These measures illustrate how authorities viewed student organizations as influential actors within dissent and reform movements.

Internal culture shaped the identity of each association. Members adopted distinctive symbols such as the Farben (fraternity colors), ribbons called Band (fraternity sash), and embroidered caps known as Mütze (fraternity cap). Rituals reinforced group cohesion, including formal meetings, ceremonies, and the practice of regulated dueling known as Mensur (academic fencing). While the Mensur’s significance varies across organizations, it historically symbolized discipline, courage, and adherence to group norms. These traditions underline the structured, ceremonial character of fraternity life in German universities.

Academic and moral expectations also played a central role. Many Burschenschaften promoted Bildungsbürgerlichkeit (educated middle-class values), emphasizing scholarship, ethical conduct, and civic engagement. Members were encouraged to participate in public discourse, pursue professional careers, and contribute to social development. This connection between academic identity and public responsibility continues to shape the internal mission of many associations, even as social and political contexts have evolved.

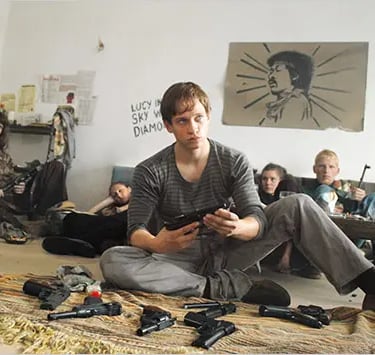

The twentieth century brought periods of tension and transformation. During the National Socialist era, many Burschenschaften faced pressure to conform to state ideology, leading to dissolution or forced alignment. After 1945, organizations re-established themselves within democratic frameworks, often engaging in debates concerning historical responsibilities, political orientation, and the meaning of tradition. Contemporary Burschenschaften vary widely in structure, political stance, and membership, reflecting broader pluralism within academic life. Some focus primarily on heritage and networking, while others emphasize civic education or historical research.

CURRYWURST

Currywurst (curried sausage) refers to a widely popular German fast-food dish consisting of sliced pork sausage covered in a spiced tomato-based sauce. Originating in the mid-twentieth century, it has become one of the most recognizable examples of German street food culture. The dish is closely associated with post-war Berlin, where vendor Herta Heuwer created an early version in 1949 by combining ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, and curry powder. Its rapid spread across cities illustrates broader social and economic developments in the reconstruction period, when affordable, filling foods gained strong public appeal. Currywurst remains a staple of snack stands, food kiosks, and quick-service restaurants throughout the country.

The sauce, known as Currysauce (curry sauce), is fundamental to the dish’s identity. It typically contains tomato paste, vinegar, sugar, spices, and varying quantities of curry powder. Regional preferences influence sweetness levels, acidity, and spiciness. Some establishments add Paprikapulver (paprika powder) or Chilipulver (chili powder) to produce sharper flavors, while others use mild blends suited to broader audiences. Variations illustrate how local tastes shape fast-food traditions, despite the dish’s standardized basic components. The sauce is usually warmed and poured over the sliced sausage immediately before serving, creating a distinctive aromatic combination.

The sausage component, called Bratwurst (grilled sausage), varies across regions. In Berlin and northern Germany, a boiled, fine-textured pork sausage is common, often without casing. In western regions, grilled sausages with crispy skins appear more frequently. Food vendors typically prepare the dish on flat-top grills known as Bratplatte (grill plate), allowing rapid service during peak hours. The sausage is cut into bite-sized pieces and eaten with a small disposable fork, reinforcing the dish’s status as convenient street food suited to busy urban environments.

Currywurst is often accompanied by side dishes that reflect local eating habits. One widespread option is Pommes frites (French fries), usually served with sauces such as mayonnaise, ketchup, or a combination known as Pommes rot-weiß (red-white fries). In some regions, customers choose a bread roll called Brötchen (bread roll) to accompany the dish instead. These combinations highlight the adaptability of the meal within different fast-food settings, from small kiosks to large canteens and stadium concessions.

Culturally, Currywurst holds symbolic value tied to urban identity and working-class food culture. It became an essential part of everyday consumption during the economic recovery known as the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle), when quick and affordable meals supported laborers, office workers, and students. In Berlin, the dish developed into a city icon, associated with post-war resilience and the informal social fabric of food stands known as Imbiss (snack kiosks). Its representation in literature, film, and popular culture reflects a widespread recognition that reaches far beyond food itself.

DENGLISH

Denglisch (German–English hybrid language) refers to the mixture of German and English lexical elements that appears in everyday speech, business communication, advertising, youth slang, and digital media in German-speaking countries. The term is used both descriptively and critically to denote the increasing influence of English on contemporary German. This linguistic blending reflects globalization, technological development, and cultural exchange, and it raises ongoing debates about language preservation, clarity, and social identity. Denglisch is not a separate language but a fluid phenomenon that demonstrates how German adapts to new communicative contexts.

In everyday communication, Denglisch often emerges through Anglizismen (loanwords from English), which frequently replace existing German terms. Examples include expressions such as downloaden (to download) or managen (to manage), where English verbs acquire German grammatical endings. The spread of such forms is supported by the widespread use of English in fields like information technology, marketing, and science. Professional environments rely on terminology such as Meeting (meeting) and Feedback (feedback), illustrating the influence of English in workplace vocabulary. This incorporation reflects functional necessity in sectors where English serves as a lingua franca.

Advertising and branding also contribute significantly to Denglisch. Companies often employ English words to convey modernity, international appeal, or technological sophistication. Slogans and product names use hybrid forms such as Sale (sale event) or Lifestyle (lifestyle), which become integrated into consumer culture. The strategy aligns with marketing practices emphasizing global reach and youthful imagery. Critics argue that such usage may reduce linguistic precision, while supporters view it as a natural outcome of economic integration and cultural interconnectedness.

Youth culture and digital communication represent another major domain where Denglisch flourishes. Online interactions frequently incorporate expressions linked to gaming, social media, and digital platforms. Terms like liken (to like on social media) or posten (to post) exemplify this adaptation. The prevalence of English-language entertainment, including music, streaming, and gaming communities, further accelerates hybrid usage. These influences shape linguistic preferences among younger speakers and contribute to generational differences in language habits.

Debates concerning Denglisch often center on linguistic policy and preservation. Institutions responsible for language norms, including the Dudenredaktion (Duden editorial board), monitor the rise of English borrowings and evaluate their standardization. Some commentators advocate for replacing Anglicisms with German equivalents to maintain linguistic clarity, while others argue that languages evolve naturally through contact and adaptation.

DIRNDL

Dirndl (traditional women’s dress) refers to the regional costume worn primarily in Bavaria and Austria, consisting of a fitted bodice, blouse, full skirt, and apron. Originally derived from rural work clothing of the nineteenth century, the garment gradually developed into a symbol of alpine cultural identity. Its construction reflects historical tailoring practices in rural communities, where durable fabrics and practical cuts supported daily agricultural labor. Over time, urban fashion movements adopted and stylized the garment, transforming it from simple workwear into a recognized element of regional tradition.

The structure of a Dirndl is defined by several key components. The Mieder (bodice) fits closely to the upper body and may be laced, buttoned, or hooked, depending on regional style. Beneath the bodice is the Bluse (blouse), typically white and cropped, with sleeves and neckline shapes varying according to tradition or personal preference. The skirt, called the Rock (skirt), is gathered to create volume and allow freedom of movement. The outfit is completed by the Schürze (apron), which provides both decoration and functional layering. These elements together create the recognizable silhouette associated with alpine dress.

Regional differences contribute to the diversity of Dirndl styles. In Salzburg and Upper Austria, darker colors and modest cuts prevail, reflecting conservative rural traditions. In Bavaria, especially around Munich, brighter fabrics and decorative embroidery appear more frequently. These differences are further expressed through patterns such as checks, stripes, and floral prints. Accessories like the Charivari (decorative chain) add distinctive features, often incorporating small charms or coins that reference family history or local craft traditions.

The symbolism of the apron knot plays a notable role in social customs. The position of the Schleife (bow) may indicate aspects of the wearer’s status in traditional contexts. A bow tied on the right side is commonly interpreted as signifying that the wearer is in a relationship, while a bow on the left is associated with being single. Although not universally applied, this convention appears frequently in festival settings and contributes to the cultural meaning attached to the Dirndl.

Today, the garment is worn most prominently during regional festivals such as Oktoberfest and local Volksfest (folk festival) celebrations. Commercial designers produce modern interpretations with updated fabrics and fashion elements, while traditional tailors maintain historical forms.

DORFMENTALITÄT

Dorfmentalität (village mentality) refers to social attitudes and behavioral patterns typically associated with life in small rural communities in German-speaking regions. The term is often used to describe the close-knit, familiar, and sometimes conservative character of village society. It highlights how geographic scale, social proximity, and long-term interpersonal relationships influence community dynamics. Dorfmentalität is not a formal sociological category but a widely recognized cultural concept that helps explain differences between rural and urban lifestyles.

A key feature of Dorfmentalität is the emphasis on Nachbarschaft (neighborly relations), where residents know one another personally and engage in regular face-to-face interactions. These relationships can foster trust, mutual support, and shared responsibility. Practices such as assisting with agricultural tasks, participating in local events, or engaging in informal exchanges reinforce social cohesion. The familiarity among residents often leads to strong community monitoring, sometimes described as soziale Kontrolle (social oversight), reflecting the tendency for individual actions to be visible within a small population.

Tradition plays a substantial role in shaping local identity. Cultural customs, seasonal celebrations, and religious events remain central to village life, supported by associations known as Vereine (local clubs). These include volunteer fire brigades, music groups, and sports clubs, which serve as focal points for social interaction. Participation in Vereine reinforces a sense of belonging and maintains continuity across generations. Such structures illustrate how community organization in rural areas differs markedly from anonymous urban settings.

At the same time, Dorfmentalität can imply certain limitations or social expectations. The preference for established norms may contribute to Konformitätsdruck (pressure to conform), where deviation from community standards attracts attention or criticism. Newcomers sometimes face integration challenges due to long-standing social networks that shape local hierarchies. These dynamics help explain why rural communities may appear resistant to change, innovation, or external influences, even as they maintain strong internal cohesion.

Economic and demographic factors further influence the concept. Many villages have experienced population aging and outmigration as younger residents move to urban centers for employment or education. This shift affects the sustainability of local services such as Grundversorgung (basic services), including shops, schools, and medical practices.

EDELWEISS

Edelweiß (alpine edelweiss flower) refers to the small, white, star-shaped plant that grows in high alpine regions of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Recognized for its woolly petals and resilience in harsh climates, it has become one of the most emblematic symbols of the Alps. The plant thrives in rocky habitats above the tree line, where cold temperatures, strong winds, and intense sunlight shape its biological characteristics. Its limited natural range contributes to its status as a protected species under regional conservation laws.

Botanically, the Edelweiß belongs to the genus Leontopodium. Its distinctive appearance comes from the Filzhaare (felt-like hairs) that cover its leaves and bracts, helping the plant retain moisture and shield itself from ultraviolet radiation. These adaptations reflect survival strategies in extreme alpine environments. The flower typically grows in clusters along limestone outcrops, contributing to the fragile ecosystem known as Alpinrasen (alpine grassland), an environment sensitive to erosion and human activity.

The cultural significance of Edelweiß is deeply rooted in alpine traditions. Historically, it served as a symbol of Tapferkeit (bravery), since collecting the flower required climbing steep and dangerous slopes. This association appears in folklore, music, and regional literature. During the nineteenth century, the flower became linked to emerging ideas of national identity in the alpine regions, often representing purity, loyalty, and attachment to homeland. In many areas, it is connected to the concept of Heimat (homeland), illustrating emotional ties to mountain landscapes.

Military history also played a role in shaping the flower’s symbolism. Certain alpine units used the Edelweiß as an insignia, known as the Edelweißabzeichen (edelweiss badge), worn on uniforms to signify connection to mountain warfare traditions. This usage contributed to its recognition throughout German-speaking countries and reinforced associations with endurance and resilience. At the same time, conservation concerns increased as the flower became a sought-after souvenir among tourists.

Modern conservation measures protect wild populations. Edelweiß is included in regional protection lists enforced by Naturschutzgesetz (nature protection law), which restricts collection and regulates alpine tourism. Educational programs and nature reserves emphasize the importance of preserving fragile alpine habitats. Cultivated varieties now appear in gardens and alpine botanical collections, reducing pressure on wild populations while allowing public access to the plant’s visual appeal.

In contemporary culture, the Edelweiß remains a widely used emblem in tourism, regional branding, and traditional crafts. It appears on textiles, jewelry, and festival decorations, especially in Bavaria and Tyrol. Musicians and folk groups incorporate the flower into performances linked to Volksmusik (folk music), reinforcing its role in alpine cultural identity.

FACHWERKHAUS

Fachwerkhaus (half-timbered house) refers to the traditional architectural style in which load-bearing wooden beams create a visible structural framework filled with materials such as wattle-and-daub, brick, or plaster. This construction method has been used in German-speaking regions for centuries and remains one of the most recognizable features of historical townscapes. The design reflects local craftsmanship, available materials, and building techniques shaped by regional climates and cultural traditions. Fachwerkhäuser appear in both rural villages and historic urban centers, forming a key component of Germany’s architectural heritage.

The structural system is defined by the Holzrahmen (timber frame), consisting of vertical posts, horizontal beams, and diagonal braces that provide stability. The infill, known as the Gefach (panel between beams), traditionally used clay mixed with straw, creating an insulating but lightweight wall. Over time, brick and stone became common in certain regions, especially where clay was less available. The visible wood pattern often forms decorative geometric motifs, illustrating the aesthetic dimension of structural engineering. Craftsmen used techniques such as the Zapfenverbindung (mortise-and-tenon joint), ensuring durability without modern fasteners.

Regional variations illustrate the diversity of this building tradition. In Hesse and Thuringia, dark timber with white plastered panels creates a striking contrast, while in Alsace and Baden-Württemberg, colored facades and ornate carvings appear more frequently. Northern Germany features Niederdeutsches Hallenhaus (Low German hall house), incorporating large central halls for mixed residential and agricultural use. In Franconia, the Fränkischer Dreiseithof (Franconian three-sided farmstead) integrates multiple Fachwerk structures around a courtyard. These differences reflect agricultural practices, climate, and social organization in each region.

Urban Fachwerkhäuser often occupy narrow plots shaped by medieval street layouts. Many towns preserve rows of such buildings forming historical ensembles protected under Denkmalschutz (monument protection law). Cities like Quedlinburg, Goslar, and Limburg an der Lahn maintain extensive Fachwerk districts that illustrate building traditions spanning several centuries. Preservation includes careful documentation, restoration methods, and the use of traditional materials to maintain authenticity. Techniques such as Lehmputz (clay plaster) and natural wood treatments ensure compatibility with historical construction.

The endurance of Fachwerkhaus architecture also relates to its functional qualities. The wooden frame provides flexibility that allows buildings to withstand structural movement, while breathable wall materials regulate indoor climate. Historically, these properties were advantageous in regions with variable weather patterns. Modern conservation efforts emphasize these ecological benefits, aligning traditional construction with contemporary sustainability principles.

Contemporary use of Fachwerkhaus structures varies. Some serve as private residences, guesthouses, or cultural institutions, while others house shops or restaurants in historical town centers.

FASTNACHT

Fastnacht (pre-Lenten carnival period) refers to the traditional festive season that precedes Lent in many German-speaking regions. It is characterized by costumes, parades, music, and community celebrations rooted in centuries-old customs. The term is especially common in southwestern Germany, including Baden, Swabia, and parts of the Rhineland. Fastnacht functions both as a cultural expression and as a seasonal marker tied to the liturgical calendar. Its practices illustrate historical rhythms of rural life, social inversion, and communal identity.

A central element of Fastnacht is the use of carved wooden masks called Larven (carnival masks), worn by participants in parades and street performances. These masks represent characters associated with local folklore, historical figures, or symbolic roles such as fools and demons. Groups known as Narrenzünfte (guilds of carnival jesters) organize events, manage traditional costumes, and maintain continuity in the customs passed down across generations. Their activities reinforce regional identity and highlight the organizational structure that underlies the festivities.

Costuming plays a major role in shaping the atmosphere. Participants wear Häs (traditional carnival costume), often handmade and decorated with fabric patches, bells, or embroidered motifs. The sound of bells called Schellen (small bells) is a familiar feature of processions, intended historically to chase away winter spirits or symbolize renewal. The presence of musicians performing Guggenmusik (carnival brass music) contributes to the sonic landscape, combining humor, improvisation, and rhythmic energy. These auditory and visual elements distinguish Fastnacht from other European carnival traditions.

The festivities often follow a structured timeline influenced by local customs. Celebrations may begin on the Schmotziger Donnerstag (Fat Thursday), marking the formal onset of carnival activities. Parades, village gatherings, and symbolic rituals continue through the weekend, culminating on Rosenmontag (Rose Monday), a major day of public events in many regions. In some towns, a final procession on Shrove Tuesday is followed by the symbolic burning of a figure called the Fastnachtspuppe (carnival effigy), marking the end of festivities and the transition into Lent.

Historically, Fastnacht allowed communities to momentarily invert social hierarchies and indulge in humor, satire, and exaggeration. The tradition incorporates elements of Brauchtum (customary tradition), illustrating how rural populations managed seasonal transitions and expressed collective identity. Over time, these symbolic meanings blended with Christian liturgical practices, creating a hybrid tradition that persists today.

FEIERABEND

Feierabend (time after work) refers to the period following the end of the working day in German-speaking countries, traditionally associated with rest, personal time, and the separation between professional duties and private life. The concept carries cultural weight beyond the literal meaning of finishing work. It reflects long-standing social norms about work–life balance, community interaction, and the value placed on leisure. Feierabend functions as both a temporal marker and a cultural ideal, shaping daily routines and influencing workplace expectations.

Historically, Feierabend developed alongside industrial labor patterns. As structured working hours replaced agricultural rhythms, the end of the day became clearly defined and widely recognized. This contributed to the importance of Arbeitszeit (working hours), which delineated the boundary between labor and personal life. The transition from work to leisure was often accompanied by rituals such as communal gatherings or evening meals. In many regions, especially in small towns, the ringing of the Feierabendglocke (end-of-work bell) signaled the official close of the workday and reinforced collective timekeeping.

Feierabend is closely linked to Germany’s emphasis on maintaining a balanced lifestyle. Workers often use this period for activities that support physical and mental well-being. Visiting local pubs, participating in sports clubs known as Sportverein (sports association), or spending time with family are typical ways of structuring the evening hours. These routines highlight the cultural preference for predictable daily structures and help distinguish the private sphere from occupational obligations. Feierabend remains central to discussions about health, productivity, and social cohesion.

The concept also shapes workplace culture. Employers and employees generally respect boundaries associated with Feierabend, and in many sectors it is customary not to contact colleagues after hours except in urgent cases. This expectation is intertwined with the principle of Erholungszeit (recovery time), an idea embedded in labor law and collective agreements. Such norms contribute to lower levels of after-hours work compared to countries with more flexible or undefined working schedules. The cultural consensus around maintaining a clear division between work and leisure reinforces social stability and personal autonomy.

Recreational activities during Feierabend vary widely. Some individuals pursue hobbies such as Vereinsleben (club life), which includes participation in music groups, volunteer fire brigades, or cultural associations. Others focus on household responsibilities or enjoy simple relaxation at home. The evening meal plays a notable role in many households, particularly the tradition of Abendbrot (evening bread meal), consisting of bread, cold cuts, and simple accompaniments. This routine underscores how Feierabend integrates social interaction with everyday domestic practices.

In contemporary society, digital communication and flexible work arrangements challenge traditional boundaries. Remote work, mobile devices, and global business hours can blur distinctions between professional and personal time. Discussions in labor policy increasingly address issues related to the Recht auf Abschalten (right to disconnect), reflecting concerns about burnout and constant availability.

FLAMMKUCHEN

Flammkuchen (Alsatian-style flatbread) refers to a thin, crisp baked dish originating from the region historically known as Alsace, which today spans areas of France and southwestern Germany. It is traditionally prepared with a very thin dough topped with cream, onions, and bacon before being baked at extremely high temperatures. The dish developed from practical baking routines in rural communities, where bakers tested oven heat with small pieces of dough before baking bread. These early tests evolved into a recognizable regional specialty that remains widely consumed in both domestic and commercial settings.

The dough forms the foundation of Flammkuchen. It is typically made without yeast, producing a thin, elastic sheet that becomes crisp when placed in a hot oven. Bakers traditionally use a Holzofen (wood-fired oven), which reaches high temperatures and imparts a distinct smoky flavor. The thinness of the dough distinguishes the dish from pizza and other flatbreads, reinforcing its identity within regional culinary traditions. The simplicity of the dough also highlights the resourcefulness of rural households that relied on minimal ingredients for everyday cooking.

The topping known as Schmand (sour cream mixture) provides the characteristic creamy base. It is often blended with crème fraîche to create a balanced texture. Onions sliced into thin rings and bacon strips called Speck (cured bacon) complete the classic version. These ingredients reflect local agricultural production, particularly dairy farming and pig husbandry, which shaped regional food availability. Variants exist across the Upper Rhine region, but the essential combination of cream, onions, and bacon defines the traditional preparation.

Regional adaptations demonstrate the dish’s versatility. In some areas, sweet versions appear, using apples, cinnamon, and sugar. Modern restaurants introduce toppings such as mushrooms, goat cheese, or seasonal vegetables. Despite these innovations, the original version known as Elsässer Flammkuchen (Alsatian-style flammkuchen) remains the most recognized. The dish often appears in wine taverns and village festivals, where it pairs with local white wines. This association reflects broader gastronomic traditions of the region and reinforces cultural links across the Rhine valley.

Cultural significance also extends to communal eating practices. Flammkuchen is frequently served in large portions meant for sharing, contributing to its role in social gatherings. Its quick baking time supports informal dining, especially in settings where ovens remain central to community events. In rural areas, traditional baking days called Backtag (baking day) often featured Flammkuchen alongside bread production.

FREIKÖRPERKULTUR

Freikörperkultur (free body culture) refers to the German naturist movement emphasizing non-sexual social nudity in designated public or semi-public spaces. The practice emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as part of broader reforms focused on health, physical exercise, and natural living. It reflects ideas about body acceptance, equality, and a return to nature. In Germany, FKK developed distinct cultural legitimacy, supported by associations, beach areas, and wellness facilities that normalize non-sexual nudity as a form of recreation and community participation.

Health reform movements played a significant role in shaping the early development of Freikörperkultur. Advocates promoted Lichtluftbad (light-and-air bath), a practice emphasizing sun exposure and fresh air as beneficial to physical well-being. Organizations established dedicated spaces where nudity was permitted under regulated conditions. These associations, known as Naturistenverein (naturist clubs), provided structured environments for families and individuals to participate in outdoor activities such as swimming, sunbathing, and sports. Their growth reflects cultural interest in natural lifestyles and physical health.

FKK also developed within specific social and political contexts. During the Weimar Republic, the movement expanded as part of broader cultural experimentation and social liberalization. Later, in the German Democratic Republic, naturism became a widely accepted recreational activity, particularly along the Baltic Sea coastline. In that context, FKK was associated with Gleichberechtigung (equality), as it provided a space where social differences appeared minimized through shared participation. Its popularity in East Germany contributed to a unique regional identity that continues to influence contemporary practices.

Regulations govern where nudity is permitted. Municipal guidelines and park rules define FKK-Bereich (designated nudist area), ensuring that naturist zones coexist with textile (clothed) areas without conflict. Many lakes, beaches, and recreation areas maintain clearly marked sections, providing predictability and comfort for participants and non-participants. Saunas, wellness centers, and thermal baths frequently follow the Saunakultur (sauna culture) tradition, where nudity is mandatory rather than optional, emphasizing hygiene and equality rather than display or exhibition.

FKK emphasizes specific social norms regarding behavior. Participants adhere to principles of respect, discretion, and non-sexual conduct. Photography is typically restricted, and interactions follow expectations common in other recreational settings. These norms support the understanding of nude recreation as an ordinary communal activity rather than a form of provocation.

Today many traditional naturist clubs remain active, and FKK beaches persist along the Baltic and North Sea coasts. At the same time, shifts in urban lifestyles and increased international tourism introduce new perspectives on nudity and public space.

FRÜHSCHOPPEN

Frühschoppen (morning social drinking) refers to a traditional gathering held late in the morning, typically on Sundays or holidays, in many German-speaking regions. The custom involves meeting in taverns, beer halls, or community venues to drink beer, eat simple foods, and engage in social conversation. Frühschoppen has deep historical roots tied to rural life, religious practice, and community cohesion. Although participation varies by region, it continues to represent an important form of social interaction, particularly in Bavaria and Austria.

The cultural context of Frühschoppen is shaped by communal routines. Historically, it followed church attendance, allowing villagers and families to transition from religious observance to social gathering. This rhythm contributed to the association between Frühschoppen and Geselligkeit (social conviviality), emphasizing relaxed conversation and shared leisure. Music often plays a role, especially traditional brass ensembles known as Blaskapelle (brass band), which perform at festivals or special events. Their presence reinforces the celebratory atmosphere typical of these gatherings.

Beverage traditions form a central component. Participants commonly drink local beer, especially Weißbier (wheat beer), which has long been associated with morning consumption in Bavaria. The choice reflects both regional brewing practices and historical norms regarding alcohol and daily life. Frühschoppen may also include non-alcoholic options, but beer remains the defining element of the custom. Food accompanies the drinks, typically regional specialties such as sausages, pretzels, or cold cuts. These foods align with the concept of Brotzeit (snack meal), a light, savory meal suited to social occasions.

Regional differences influence how Frühschoppen is practiced. In Franconia and Upper Bavaria, gatherings often take place in beer gardens or rural inns, whereas in Austria, they may be part of local festivals or market days. In some areas, the event is linked to agricultural life, reflecting the social bonds within farming communities. In others, it has adapted to urban environments, appearing in city beer halls. These variations illustrate how local culture shapes the specific form of the tradition while maintaining its core elements.

The social function of Frühschoppen extends beyond leisure. It provides a venue for community discussion, informal networking, and local decision-making. Historically, such gatherings contributed to Dorfleben (village life), acting as spaces where news circulated and communal relationships strengthened. Even today, many associations, including sports clubs and volunteer fire brigades, use Frühschoppen events to raise funds or celebrate milestones.

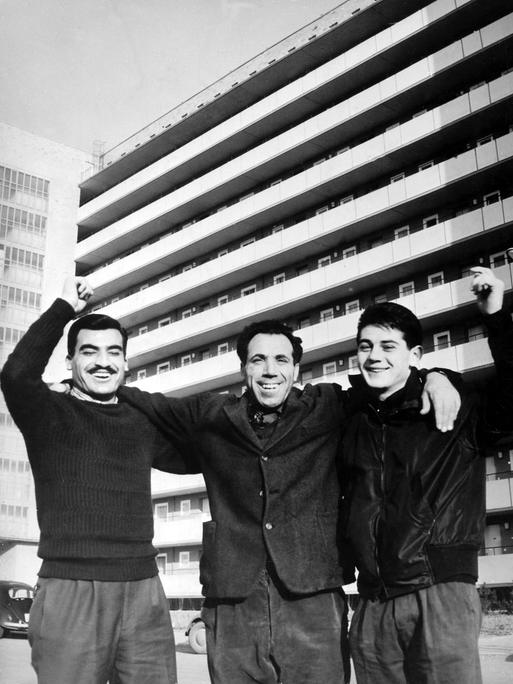

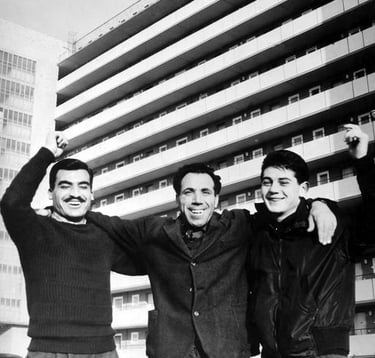

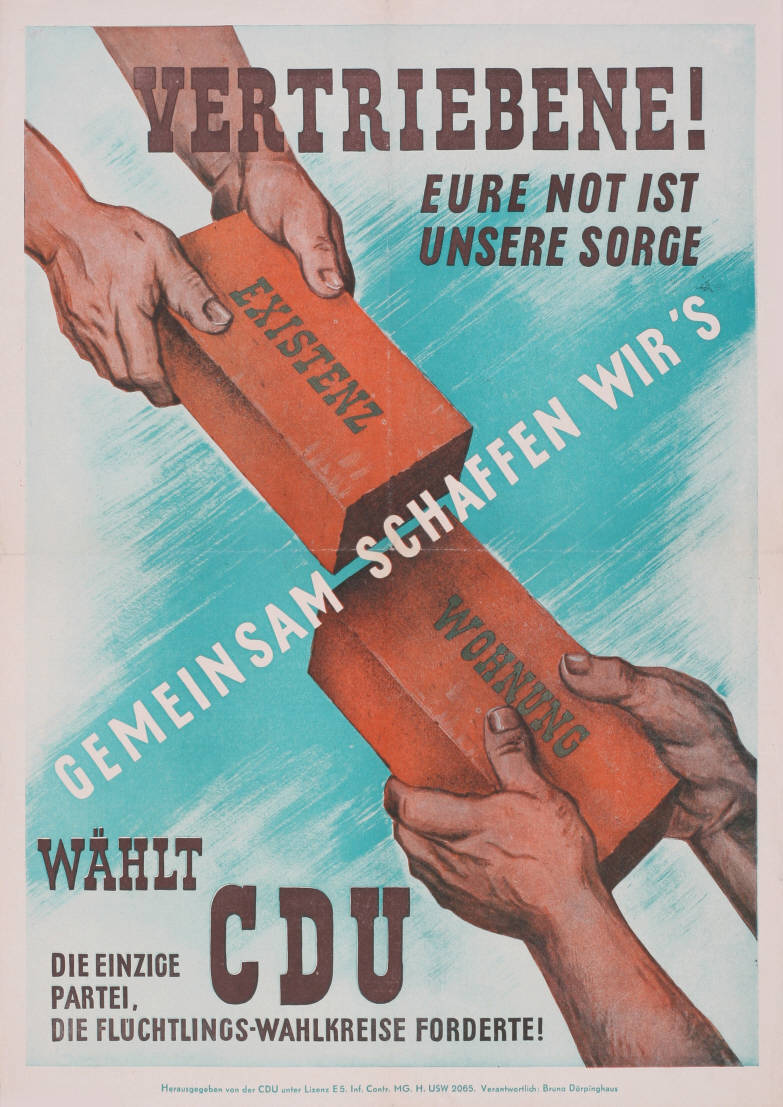

GASTARBEITER

Gastarbeiter (guest worker) refers to the foreign workers recruited to West Germany during the post-war economic expansion of the 1950s and 1960s. The term originally described temporary labor migrants invited through bilateral agreements to fill shortages in industrial sectors, particularly manufacturing, mining, and construction. Although the intention was short-term employment, many Gastarbeiter settled permanently, shaping the demographic, cultural, and economic landscape of modern Germany. The program reflects both the labor demands of the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle) and the broader dynamics of migration in post-war Europe.

Recruitment began with Italy in 1955 and later expanded to countries such as Spain, Greece, Turkey, and Yugoslavia. These agreements aimed to regulate the flow of workers while providing structured employment opportunities abroad. Under the system of Rotation (rotation principle), workers were expected to stay for limited periods before returning home, allowing German employers to maintain a flexible workforce. Over time, however, the rotation principle proved impractical, as trained workers gained skills that industries preferred to retain. This contributed to long-term settlement and family reunification.

Working conditions varied by sector but typically involved demanding physical labor. Gastarbeiter often took positions classified as ungelernte Tätigkeiten (unskilled occupations), though many possessed valuable experience or training. They frequently lived in company-owned dormitories called Wohnheim (worker housing), designed to accommodate temporary workers. Despite the challenges, these jobs provided higher wages compared to earnings in countries of origin, contributing to remittances that supported families abroad. At the same time, workplace experiences shaped patterns of social integration within German society.

Legal frameworks influenced the status and rights of guest workers. Initially, residence permits were tightly linked to employment contracts, limiting mobility between sectors and employers. As settlement increased, policies gradually shifted toward family reunification and social inclusion. Education systems adapted to support children of migrant families through initiatives such as Förderunterricht (remedial instruction) and bilingual programs. These developments reflect the transition from temporary labor migration to the establishment of long-term migrant communities.

Cultural impact forms a significant part of the Gastarbeiter legacy. Migrants introduced new foods, music, and cultural practices that blended with existing local traditions. Restaurants, shops, and community associations founded by former guest workers contributed to urban cultural diversity. The influence of Turkish migrants, in particular, became prominent, with traditions such as Teestube (tea house) and regional cuisines becoming integrated into everyday German culture.

JODELN

Jodeln (yodeling) refers to the vocal technique characterized by rapid alternation between chest voice and head voice, producing distinct breaks in pitch. It is traditionally associated with alpine regions of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, where it developed as both a practical form of long-distance communication and a cultural expression. The technique involves controlled shifts called Registerwechsel (register changes), which allow singers to project sound across valleys and mountainous terrain. Jodeln remains an important component of alpine musical identity and continues to be practiced in both traditional and modern contexts.

Historically, Jodeln served functional purposes. Shepherds and herders used vocal calls known as Lockrufe (herding calls) to communicate with animals or signal across long distances. These calls evolved into recognizable melodic patterns, shaping early forms of yodeling. Over time, the technique became integrated into folk traditions, especially in rural alpine communities where communication across steep landscapes required strong, far-carrying sound. This practical origin distinguishes Jodeln from purely musical vocal styles.

Musically, the technique forms part of Volksmusik (folk music), where it appears in ensemble pieces, dance tunes, and solo performances. Traditional groups often include instruments such as the accordion, zither, and alpine horn. The alpine horn, referred to as Alphorn (alpine horn), complements yodeling because of its ability to project tones over long distances and its historical association with pastoral life. Yodeling styles vary according to region, with some emphasizing melodic ornamentation and others focusing on rhythmic patterns.

Regional diversity plays a significant role in shaping Jodeln. In Bavaria, styles known as Jodler (yodel song) are integrated into local festivities and often performed in taverns, festivals, and alpine gatherings. In Austria’s Salzkammergut region, more elaborate polyphonic forms such as Mehrstimmiger Jodler (multi-voiced yodel) have developed, featuring harmonized calls by multiple singers. Swiss traditions place emphasis on precise tonal purity and slower, more resonant melodies. These variations illustrate how geography and community practices influence performance techniques.

Cultural significance extends to social life and identity. Jodeln is commonly performed at regional events such as Almabtrieb (ceremonial cattle drive), harvest festivals, and folk gatherings. Performances reinforce a shared sense of heritage and emphasize the continuity of alpine traditions across generations. The practice also appears in competitions and cultural clubs, many organized under associations dedicated to preserving regional music. These institutions support instruction, research, and performance standards.

GUMMIBÄRCHEN

Gummibärchen (gummy bears) refers to small, fruit-flavored gelatin candies that originated in Germany and became one of the most internationally recognized confectionery products. First introduced in the 1920s, these candies were created by Hans Riegel, founder of the company Haribo. Their distinctive bear shape and chewy texture quickly gained popularity and remain central to German sweets culture. Gummibärchen reflect developments in food manufacturing, marketing, and consumer preferences across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The composition of Gummibärchen relies on a combination of gelatin, sugar, glucose syrup, and flavorings. Gelatin provides the elastic texture characteristic of gummy candies, while natural or artificial colorants produce the vibrant appearance associated with each flavor. Modern manufacturing facilities use Gelierverfahren (gelatin-setting process), where heated mixtures are poured into bear-shaped molds made of starch. After cooling and drying, the candies are coated with a thin layer of beeswax or carnauba wax to create a smooth, shiny surface. These production techniques reflect the evolution of industrial confectionery methods in Germany.

Flavor diversity contributes to the product’s enduring appeal. Traditional assortments include lemon, orange, raspberry, strawberry, and pineapple. Over time, expanded lines have introduced new flavors and variations, including sour, sugar-free, and juice-based versions. These developments respond to changing consumer demands and reflect innovation in Lebensmitteltechnologie (food technology). Seasonal editions, regional specialities, and limited-release products further illustrate the adaptability of Gummibärchen within contemporary markets.

Culturally, Gummibärchen hold a strong position in German daily life. They are commonly sold in supermarkets, kiosks, and bakeries, and often appear in school lunchboxes, office snacks, and household treat jars. The association with childhood is particularly strong, supported by advertising campaigns and the presence of the Goldbär (golden bear) mascot, which represents the brand’s identity. The candy’s widespread appeal underscores its integration into German consumer culture and its nostalgic value for many generations.

International expansion has also shaped the product’s significance. Haribo factories now operate across Europe, North America, and Asia, introducing Gummibärchen to global markets. The brand’s slogan Haribo macht Kinder froh (Haribo makes children happy) has become widely recognized and adapted into various languages. This global reach highlights Germany’s influence on modern confectionery trends and demonstrates how a locally developed product can achieve worldwide cultural presence.

Debates surrounding health and nutrition occasionally engage with gummy candies. Discussions focus on sugar content, artificial additives, and the role of sweets in children’s diets. In response, manufacturers have introduced versions with reduced sugar, natural colorings, or alternative gelling agents.

KARNEVAL

Karneval (carnival season before Lent) refers to the festive period leading up to Lent in many German-speaking regions, especially in the Rhineland. It is characterized by costumes, parades, satire, music, and public celebrations. The tradition has medieval roots and combines pre-Christian seasonal rites with Christian liturgical calendars. Today, Karneval plays a major role in regional identity, especially in Cologne, Düsseldorf, and Mainz, where it forms a distinct cultural institution. The season reflects social inversion, humor, and collective participation.

The official season begins on 11 November at 11:11 a.m., marked by the proclamation of Sessionseröffnung (opening of the carnival season), although major festivities occur in the week before Ash Wednesday. Organized groups known as Karnevalsgesellschaft (carnival societies) coordinate events, plan parades, and maintain traditions. These associations have roots in nineteenth-century civic organizations that formalized carnival customs and integrated satire, music, and symbolic figures into public celebrations.

Costuming plays a central role. Participants wear Kostüm (carnival costume), ranging from humorous outfits to elaborate handcrafted designs. Many costumes feature regional motifs, political caricatures, or traditional characters. A key figure is the Prinz Karneval (carnival prince), who symbolizes festive authority during the season. In the Rhineland, the formal trio known as the Dreigestirn (carnival triumvirate), consisting of the Prince, the Peasant, and the Maiden, presides over official celebrations and embodies civic pride.

Parades, particularly the large Rosenmontag procession, form the highlight of Karneval. Floats known as Festwagen (parade floats) carry satirical sculptures that comment on politics, society, and international events. Participants distribute sweets called Kamelle (carnival candies) to spectators along the route. Brass bands, dance groups, and walking formations contribute to the musical and visual spectacle. These elements reflect the role of Karneval as a medium for satire, civic engagement, and collective entertainment.

Music strengthens the festive atmosphere. Songs known as Karnevalsschlager (carnival hits) are composed specifically for the season and are performed in pubs, halls, and open-air events. Their themes emphasize humor, togetherness, and regional pride. Live performances in decorated venues called Sitzungssaal (carnival hall) combine music with speeches, sketches, and dance. The speeches, collectively referred to as Büttenrede (comic carnival speech), rely heavily on wordplay and social commentary.

Daily life in carnival regions adapts to the celebrations. Schools, offices, and businesses often close or operate on reduced schedules during peak days. Street festivals encourage widespread participation, with locals and tourists filling city centers to watch parades and attend public events. The custom fosters Gemeinschaftsgefühl (sense of community), reinforcing connections that extend beyond the festivities.

KATZENJAMMER

Katzenjammer (severe hangover) refers to the unpleasant physical and mental condition experienced after excessive alcohol consumption. The term is widespread in German-speaking regions and has both colloquial and historical significance. Although used humorously in everyday conversation, Katzenjammer carries older associations with emotional distress and discord. Its modern meaning reflects cultural attitudes toward drinking, social behavior, and the physical consequences of alcohol consumption. The concept appears in medical, linguistic, and cultural discussions.

Etymologically, Katzenjammer derives from the combination of “cat” and “lament,” originally describing discordant or wailing sounds. This meaning extended metaphorically to describe emotional turmoil, especially in nineteenth-century literature. Over time, it became associated with the symptoms of a hangover, reflecting public awareness of alcohol’s effects on the body. The transition illustrates a linguistic shift within Umgangssprache (colloquial language), where expressive imagery became linked to everyday experiences.

Physiologically, Katzenjammer relates to dehydration, metabolic processes, and the effects of byproducts from alcohol breakdown. These factors contribute to headaches, nausea, fatigue, and cognitive impairment. Scientific terminology classifies such symptoms under Alkoholkater (alcohol hangover), a term used in medical and health literature. Research on the causes of hangovers highlights the role of congeners, sleep disruption, and inflammatory responses. These findings demonstrate the intersection of cultural terminology with medical understanding.